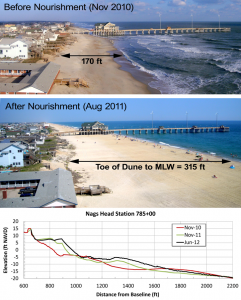

Edisto Beach before nourishment, Feb 2006

Edisto Beach was first nourished in 1954 using a borrow area in the marsh directly behind the oceanfront. The 1954 project pumped 854,000 cy of sand, shells, and mud onto the northern two miles of shoreline. While much of this volume eroded quickly because of its mud content, enough sand and shells remained trapped between groins to create a stable beach. Between 1954 and 2005, a minimal beach was maintained, but it was insufficient to offer any protection during storms. High tides reached porch steps, so numerous bulkheads and revetments were installed to prevent further encroachment.

Besides shells pumped from the salt marsh in 1954, shells from Edingsville Beach (a washover barrier fronted by marsh outcrops) are transported downcoast to Edisto Beach, giving its beach a character much different from other South Carolina beaches. Coarse shell fragments concentrate in groin fillets, increase the porosity of the beach, and lead to a steeper profile than normal. As a result, Edisto Beach has one of the narrowest wet-sand beaches in the state. (Kiawah Island and Hilton Head Island have intertidal “wet” beaches averaging over 400 ft wide, whereas Edisto Beach is typically less than 150 ft wide.) Shells and sharks’ teeth have made Edisto Beach a paradise for collectors, but the resulting steep profile also presents challenges for beach building.

A fundamental goal of beach nourishment is to match the sediment grain size and color of the borrow material with the textures of the native beach. If this is done, the nourished beach will perform as well as the native beach, particularly if the project extends for miles along the coast. (Projects of short length never perform as well because the bulge of sand produced by nourishment becomes a focus for waves and erosion.) Another reason to attempt a match of sediment textures is to create a nourished beach that is indistinguishable from the native beach.

Edisto Beach after nourishment, Jun 2006

CSE initiated a search for nourishment sand off Edisto Beach in 1990. While huge deposits exist in the shoals of St. Helena Sound, most consist of silty, fine sand – a material that would alter the character of Edisto Beach and would be quite unstable as nourishment sand. Fortunately, CSE was able to identify and confirm one compatible deposit that closely matches the native sediment texture. This limited area was used for a small nourishment involving only 150,000 cy in 1995. The borrow area was a dynamic shoal at the edge of a navigable channel, accessible to ocean-going dredges. The 1995 project demonstrated the suitability of the borrow source and had the added advantage of being a renewable resource. Soon after excavations, the 1995 dredged pit infilled with coarse sand.

Sediment borings by CSE between 2003 and 2005 confirmed an expanded borrow area in the same vicinity which closely matched the native beach. When the Illinois anchored for work in late March 2006, the GLD&D crew knew what to expect. However, most folks at Edisto Beach were caught by surprise.

For at least 40 years, vistas along the beach were interrupted by timber and rock groins projecting as much as 8 ft above the sand level. People sitting on the beach were used to seeing only as far as the nearest groin. The 2006 nourishment almost completely buried the groins. For the first time in years, crowds several groin cells away looked as if they were on the same section of beach. And oceanfront property owners could look over an expanse of dry beach with the satisfaction of knowing the beach is higher along with their property values.

Edisto Beach before nourishment, Feb 2006

Many ask how long Edisto’s new beach will last. The answer is not simple because, in simple terms, Edisto’s natural erosion rate varies greatly from north to south. Before groins were built, the northern end along the state park eroded at over 10 ft per year (ft/yr). The center of the island changed very little and the downcoast shoreline actually accreted over decades.

Groins (constructed in the 1950s and 1960s) modified shoreline change rates to the point that natural rates were masked. Now that the groins are mostly buried, one could expect to see larger fluctuations in erosion rates, high erosion (ie, >5 ft/yr) at the updrift end of the project, and accumulation of nourishment sand at the southern (downcoast) end of the island. If your area of interest is the center of the island, you will probably see little change over the next several years. Where erosion occurs, the rate is expected to decline in relation to the degree of exposure of the groins. In other words, as the groins are uncovered, they become more effective sand traps.

What’s Next for Edisto Beach?

CSE will closely monitor the new beach over the next several years. Surveys will answer the question: “How fast is the beach eroding?”

The town would like to obtain federal funding for a “50-year” project (cost shared among federal, state, county, and municipal sources) and has entered into discussions with the US Army Corps of Engineers.

Edisto Beach after nourishment, Jun 2006

Other alternatives being investigated are extensions to the existing groins. Longer groins would trap and hold the nourishment sand, increasing the time before renourishment is needed. If a wider beach can be maintained, efforts can shift to dune building and better storm protection.

Even with the new beach in place, many properties remain vulnerable and will sustain damages during a hurricane. However, experience has shown that the damages will be lessened by the presence of a wider beach.